The History of the Walloon People in Belgium. Jean Philippe Soquet was Walloon.

The History of the Walloon People in Belgium. Jean Philippe Soquet was Walloon.

In Wisconsin: it is estimated that between 5,000 and 7,500 Brabantines and Hesbignons answered the call of the New World from 1852 to 1856. Algoma, Brussels, Casco, Forestville, Green Bay, Kewaunee, Luxemburg, Namur, Sturgeon Bay (Françoise L’Empereur found 700 Walloon family names in the phone books of these towns)

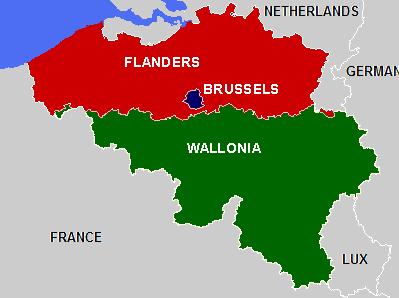

Walloons (/wɑːˈluːnz/; French: Wallons, IPA: [walɔ̃]; Walloon: Walons) are a French-speaking people who live in Belgium, principally in Wallonia. Walloons are a distinctive community within Belgium.[1] Important historical and anthropological criteria (religion, language, traditions, folklore) bind Walloons to the French people.[2][3] More generally, the term also refers to the inhabitants of the Walloon Region. They speak regional languages such as Walloon (with Picard in the West and Lorrain in the South).

Wallonia

The extent of Wallonia, the area defined by the use of the language, has shifted through the ages. The low-lying area of Flanders and the hilly region of the Ardennes have been under the control of many city-states and external powers. Such changing rule brought variations to borders, culture, and language. The Walloon language, widespread in use up until the Second World War, has been dying out of common use due to growing internationalisation. Although official educational systems do not include it as a language, the French government continues to support the use of French within the “Francophonie” commonwealth.

This is complicated by the federal structure of Belgium, which splits Belgium into three language groups with the privilege of using their own tongues in official correspondence, but also into three autonomous regions. The language groups are: French community (though not Walloon but generally named Wallonia-Brussels, see especially the international plan and from 1 January 2009)[21] Flemish community (which uses Dutch), and German-speaking community. The division into political regions does not correspond with the language-group division: “Vlaanderen” (Flanders), “la région wallonne” (Walloon region, including the German community but generally called Wallonia), and the bilingual (French-Dutch) Brussels region, also the federal capital of Belgium.

Brussels – not Walloon but mostly French-speaking

Many non-French-speaking observers (over)generalize Walloons as a term of convenience for all Belgian French-speakers (even those born and living in the Brussels Region). The mixing of the population over the centuries means that most families can trace ancestors on both sides of the linguistic divide. But, the fact that the Brussels region is around 85% French-speaking, but is located in Dutch-speaking Flanders, has led to friction between the regions and communities. The local dialect in Brussels, Brussels Vloms, is a Brabantic dialect, reflecting the Dutch heritage of the city.

Walloons are historically credited with pioneering the industrial revolution in Continental Europe in the early 19th century.[22] In modern history, Brussels has been the major town or the capital of the region. Because of long Spanish and minor French rule, French became the sole official language. After a brief period with Dutch as the official language while the region was part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, the people reinstated French after achieving independence in 1830. The Walloon region, a major coal and steel-producing area, developed rapidly into the economic powerhouse of the country. Walloons (in fact French-speaking elites who were called Walloons) became politically dominant. Many Flemish immigrants came to work in Wallonia. Between the 1930s and the 1970s, the gradual decline of steel and more especially coal, coupled with too little investment in service industries and light industry (which came to predominate in Flanders), started to tip the balance in the other direction. Flanders became gradually politically and economically dominant. In their turn, Walloon families have moved to Flanders in search of jobs.[citation needed] This evolution has not been without political repercussions.

Walloon identity

The heartland of Walloon culture is the Meuse and Sambre valleys, Charleroi, Dinant, Namur (the regional capital), Huy, Verviers, and Liège.

Regional language statistics

The Walloon language is an element of Walloon identity. However, the entire French-speaking population of Wallonia cannot be culturally considered Walloon, since a significant portion in the west (around Tournai and Mons) and smaller portions in the extreme south (around Arlon) possess other languages as mother tongues (namely, Picard, Champenois, Luxembourgish, and Lorrain). All of them can speak French as well or better.

A survey of the Centre liégeois d’étude de l’opinion[23] pointed out in 1989 that 71.8% of the younger people of Wallonia understand and speak only a little or no Walloon language; 17.4% speak it well; and only 10.4% speak it exclusively.[24] Based on other surveys and figures, Laurent Hendschel wrote in 1999 that between 30 and 40% people were bilingual in Wallonia (Walloon, Picard), among them 10% of the younger population (18–30 years old). According to Hendschel, there are 36 to 58% of young people have a passive knowledge of the regional languages.[25] On the other hand, Givet commune, several villages in the Ardennes département in France, which publishes the journal Causon wallon (Let us speak Walloon);[26] and two villages in Luxembourg are historically Walloon-speaking.

Walloons in the Middle-Ages

Since the 11th century, the great towns along the river Meuse, for example, Dinant, Huy, and Liège, traded with Germany, where Wallengassen (Walloons’ neighborhoods) were founded in certain cities. In Cologne, the Walloons were the most important foreign community, as noted by three roads named Walloon street in the city. The Walloons traded for materials they lacked, such as copper, found in Germany, especially at Goslar.

In the 13th century, the medieval German colonization of Transylvania (central and North-Western Romania) also included numerous Walloons. Place names such as Wallendorf (WalloonVillage) and family names such as Valendorfean (Wallon peasant) can be found among the Romanian citizens of Transylvania.

Walloons in the Renaissance

In 1572 Jean Bodin made a funny play on words which has been well known in Wallonia to the present:

Ouallonnes enim a Belgis appelamur [nous, les “Gaulois”], quod Gallis veteribus contigit, quuum orbem terrarum peragrarent, ac mutuo interrogantes qaererent où allons-nous, id est quonam profiscimur? ex eo credibile est Ouallones appellatos quod Latini sua lingua nunquam efferunt, sed g lettera utuntur.

Translation: “We are called Walloons by the Belgians because when the ancient people of Gallia were travelling the length and breadth of the earth, it happened that they asked each other: ‘Où allons-nous?’ [Where are we going? : the pronunciation of these French words is the same as the French word Wallons (plus ‘us’)], i.e. ‘To which goal are we walking?.’ It is probable they took from it the name Ouallons (Wallons), which the Latin speaking are not able to pronounce without changing the word by the use of the letter G.” One of the best translations of his (humorous) sayings used daily in Wallonia is “These are strange times we are living in.”

Shakespeare used the word Walloon: “A base Walloon, to win the Dauphin’s grace/Thrust Talbot with a spear in the back.” A note in Henry VI, Part I says, “At this time, the Walloons [were] the inhabitants of the area, now in south Belgium, still known as the ‘Pays wallon’.” Albert Henry agrees, quoting Maurice Piron:) also quoted by A.J. Hoenselaars “Walloon meaning Walloon country in Shakespare’s ‘Henry VI’…”[35]

The Belgian revolution

The Belgian revolution was recently described as firstly a conflict between the Brussels municipality which was secondly disseminated in the rest of the country, “particularly in the Walloon provinces”.[40] We read the nearly same opinion in Edmundson’s book:

The royal forces, on the morning of September 23, entered the city at three gates and advanced as far as the Park. But beyond that point they were unable to proceed, so desperate was the resistance, and such the hail of bullets that met them from barricades and from the windows and roofs of the houses. For three days almost without cessation the fierce contest went on, the troops losing ground rather than gaining it. On the evening of the 26th the prince gave orders to retreat, his troops having suffered severely. The effect of this withdrawal was to convert a street insurrection into a national revolt. The moderates now united with the liberals, and a Provisional Government was formed, having amongst its members Rogier, Van de Weyer, Gendebien, Emmanuel d’Hooghvorst, Félix de Mérode and Louis de Potter, who a few days later returned triumphantly from banishment. The Provisional Government issued a series of decrees declaring Belgium independent, releasing the Belgian soldiers from their allegiance, and calling upon them to abandon the Dutch standard. They were obeyed. The revolt, which had been confined mainly to the Walloon districts, now spread rapidly over Flanders.[41]

Jacques Logie wrote: “On the 6th October, the whole Wallonia was under the Provisional Government’s control. In the Flemish part of the country the collapse of the Royal Government was as total and quick as in Wallonia, except Ghent and Antwerp.”[42] Robert Demoulin who was Professor at the Université de Liège wrote: “Liège is in the forefront of the battle for liberty”,[43] more than Brussels but with Brussels. He wrote the same thing for Leuven. According to Demoulin, these three cities are the républiques municipales at the head of the Belgian revolution. In this chapter VI of his book, Le soulèvement national (pp. 93–117), before writing “On the 6th October, the whole Wallonia is free”,[44] he quotes the following municipalities from which volunteers were going to Brussels, the “centre of the commotion”, in order to take part in the battle against the Dutch troops : Tournai, Namur, Wavre (p. 105) Braine-l’Alleud, Genappe, Jodoigne, Perwez, Rebecq, Grez-Doiceau, Limelette, Nivelles (p. 106), Charleroi (and its region), Gosselies, Lodelinsart (p. 107), Soignies, Leuze, Thuin, Jemappes (p. 108), Dour, Saint-Ghislain, Pâturages (p. 109) and he concluded: “So, from the Walloon little towns and countryside, people came to the capital..”[45] The Dutch fortresses were liberated in Ath ( 27 September), Mons (29 September), Tournai (2 October), Namur (4 October) (with the help of people coming from Andenne, Fosses, Gembloux), Charleroi (5 October) (with people who came in their thousands).The same day that was also the case for Philippeville, Mariembourg, Dinant, Bouillon.[46] In Flanders, the Dutch troops capitulated at the same time in Brugge, Ieper, Oostende, Menen, Oudenaarde, Gerardsbergen (pp. 113–114), but nor in Ghent nor in Antwerp (only liberated on 17 October and 27 October). Against these interpretation, in any case for the troubles in Brussels, John W. Rooney Jr wrote:

It is clear from the quantitative analysis that an overwhelming majority of revolutionaries were domiciled in Brussels or in the nearby suburbs and that the aid came from outside was minimal. For example, for the day of 23 September, 88% of dead and wounded lived in Brussels identified and if we add those residing in Brabant, it reached 95%. It is true that if you look at the birthplace of revolutionary given by the census, the number of Brussels falls to less than 60%, which could suggest that there was support “national” (to different provinces Belgian), or outside the city, more than 40%.But it is nothing, we know that between 1800 and 1830 the population of the capital grew by 75,000 to 103,000, this growth is due to the designation in 1815 in Brussels as a second capital of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the rural exodus that accompanied the Industrial Revolution. It is therefore normal that a large part of the population of Brussels be originating provinces. These migrants came mainly from Flanders, which was hit hard by the crisis in the textile 1826-1830. This interpretation is also nationalist against the statements of witnesses: Charles Rogier said that there were neither in 1830 nor nation Belgian national sentiment within the population. The revolutionary Jean-Baptiste Nothomb ensures that “the feeling of national unity is born today.” As for Joseph Lebeau, he said that “patriotism Belgian is the son of the revolution of 1830..” Only in the following years as bourgeois revolutionary will “legitimize ideological state power.[47]

In the Belgian State

A few years after the Belgian revolution in 1830, the historian Louis Dewez underlined that “Belgium is shared into two people, Walloons and Flemings. The former are speaking French, the latter are speaking Flemish. The border is clear (…) The provinces which are back the Walloon line, i.e.: the Province of Liège, the Brabant wallon, the Province of Namur, the Province of Hainaut are Walloon […] And the other provinces throughout the line […] are Flemish. It is not an arbitrarian division or an imagined combination in order to support an opinion or create a system: it is a fact…”[48] Jules Michelet traveled in Wallonia in 1840 and we can read many times in his History of France his interest for Wallonia and the Walloons pp 35,120,139,172, 287, 297,300, 347,401, 439, 455, 468 (this page on the Culture of Wallonia, 476 (1851 edition published on line)[49]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walloons

Interact with us using Facebook